Student Workload

Synchronicity is an interesting thing. At the IR Colloquium last week I shared some preliminary data from a project I have been conducting at Victoria looking at student workload. Today I wake up to hear National Radio talking about a supposed decline in student work on their studies - based on a recent analysis published in the US. The National Radio item appears to be based essentially on a post by Dave Guerin in Education Directions, which references an article on The Chronicle of Higher Education. The problem I have is that my data suggest that, rather than declining, student study workloads are consistent with the expectation that a full-time student will work a full-time week of 40-50 hours - just like any other professional.

The US article is a meta analysis that finds:

"Using multiple datasets from different time periods, we document declines in academic time investment by full-time college students in the United States between 1961 and 2003. Full-time students allocated 40 hours per week toward class and studying in 1961, whereas by 2003 they were investing about 27 hours per week. Declines were extremely broad-based, and are not easily accounted for by framing effects, work or major choices, or compositional changes in students or schools."

Essentially, they draw on a variety of surveys, including the National Survey on Student Engagement, which ask variations of the question "how much time have you spent studying in a typical week?" Dave Guerin essentially replicated the approach on a very small scale when he compared the 2008 AUSSE results with the US ones. He took the average value for the question "About how many hours do you spend in a typical seven-day week preparing for class (e.g. studying, reading, writing, doing homework or lab work, analysing data, rehearsing and other academic activities)", got 10.5 and added an estimate of contact hours (12-16) to get 22-26 hours per week for students at Australasian institutions.

The problem with that is that in the AUSSE, students are asked three questions that speak to their study time, the one above and two others that say "Being on campus, including time spent in class" and "Being on campus, excluding time spent in class." The problem is none of these questions individually ask how much time in a typical week students spend on their studies. Each of these dances around the issue but never actually asks the question.

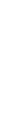

You can combine the three (on an individual student basis) and that gives a sense of what the workload might be - as in the figure below for Victoria (from the 2009 AUSSE). The problem with this is that it's likely the two "being on campus" questions overlap for some students at least - and that must be why some students appear to spend 90 hours in a typical week on their study (something I doubt very much).

The other issue is that surveys ask students questions about their workload that asks them to recall something most do not pay a lot of attention to. Their recollection is potentially going to be influenced by a number of factors including whether they enjoy the work, are engaged in their study, and their overall time-management and awareness generally. Self-reported information can also be influenced by the students' perceptions about how the information might be used, how they might be perceived on the basis of the response, and what outcomes might result from particular responses

Because of these issues I've been running a project over the last year trying to get a much richer data set on student workload. We asked students to tell us over a seven day period how they were spending their time, in 30 minute increments. The data was collected by getting the students to complete a web form at the end of each day, both to simplify data collection and recording, but also to help reduce the act of recording in a diary influencing student time use. We chose to do this in a relatively quiet week in the second term of the year to avoid any risk that participation in the project would disrupt student work.

Clearly there are some limitations even with this study. There are still issues around student recall over a day, the students were invited to participate during a lecture so students who were not attending lectures won't have been invited, and its very unlikely that students with heavy external demands from family or employment would have participated. Despite that, I think the data give a credible view of the workload experience of typical students, and they give a reasonble degree of confidence to the institution that it is possible for students to succeed while committing the sorts of time that we advise is necessary (40-50 hours per week full-time).

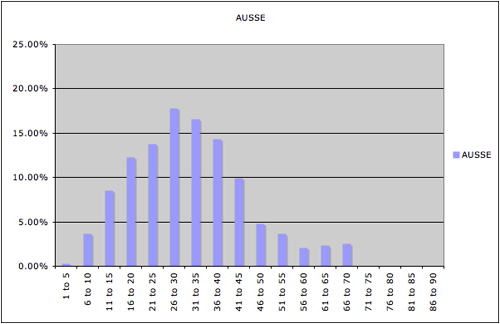

The graph below shows the results from my study plotted against the AUSSE. Interestingly they show a strong correlation, with the AUSSE results slightly higher for the population than the diary results. The increase is likely due to a combination of factors, including the overlap in the answers for individual students discussed above and the choice of a quieter week for the diary study.

So what does this all mean? Measuring workload is complex, and the literature suggests a wide variation in workload in different countries and academic contexts. I remain very sceptical about large scale survey studies despite the correlation with the AUSSE data I think individual institutions need to very carefully examine their own students' experience and carefully monitor the impact of changes in pedagogy, technology, expectations and demography.

Student workload is a complex area, it combines issues around the quantity of work, the quality of the work effort, and the perception of the workload. Students respond well to meaningful activities and will often invest significant time in them while not describing that as work, while less meaningful activities result in the perception of higher workload for fewer hours invested. Kember said it very well in 2004:

"Perceptions of workload are not synonymous with time spent studying, but can be weakly influenced by them. There are both class effects from contextual variables and individual differences within a class. Perceptions of workload are influenced by content, difficulty, type of assessment, teacher-student and student-student relationships. Workload and surface approaches to learning are interrelated, in what appears to be a complex reciprocal relationship. It is possible to inspire students to work long hours towards high quality learning outcomes if attention is paid to teaching approaches, assessment and curriculum design in the broadest sense. It is, therefore, important to have open evaluation systems which gather feedback on a wide array of curriculum variables." (Kember, D. (2004). Interpreting student workload and the factors which shape students' perceptions of their workload. Studies in Higher Education 29(2), 165-84.)