Reform of Vocational Education Submission

I was very excited when I read the Cabinet paper by Education Minister Chris Hipkins outlining his plans for a major change, dare I say it - a transformation, of the New Zealand vocational educational system. Although aimed at the failing Institutes of Technology and Polytechnic (ITPs) and Industry Training Organisations (ITOs) this ambitious proposal has important implications for universities and for New Zelaand society as a whole.

The rest of this post is the text of my submission on the proposed review, joining the hundreds of others that have been made. One submission I found very interesting was from the Office of the Auditor General which I found very much in line with my own in raising concerns about the change process and the need for clear and effective leadership. Assuming the Minister creates a transition team as recommended by OAG the composition of that team will be an important signal of how he conceives this change occuring - I do hope it goes beyond solely the vested and established interests to find people with ambitions for the public interest in this new model.

Submission Text

I am an Associate Professor at Victoria University and a researcher in the field of tertiary and higher education. I have extensively researched organisational capability and change over the last twenty years leading and advising larger scale benchmarking research projects in New Zealand and internationally. These have included assessments of organisational capability of the New Zealand University [1] and ITP [2] sectors and also longitudinal studies of change [3]. Most recently I have worked with the TEC to create a sector wide organisational capability instrument intended to engage agencies and providers with the needs of a collective national system of tertiary education responding to diverse stakeholders and operating collaboratively rather than independently [4]. This submission is undertaken in my personal academic capacity and does not reflect the views of my employer or that of any Government agency or funding body.

The need to address serious issues with the New Zealand tertiary system has been apparent for some time to those of us studying it. Research [2] on the capability of the organizations within the system, including the ITPs, has shown that they lack the capacity and will to be self-critical and respond proactively to the needs of New Zealand society. This has been driven in part by the neoliberal new public management culture of the system and declining public funding, but these are only part of the challenge facing the system [5].

The changes proposed are positive and will address issues of failed market model acknowledge in the Cabinet paper, and a CEO culture dominated by marketing and immediate profitability rather than the wider public good. However, they also risk continuing to see the system’s purpose as one of efficiently generating a qualification as a product, rather than addressing the needs of the entire community. Changes to the system need to reflect the moral limits that exist with the current market model and need to be systematically enacted through the entire institution of public tertiary education [6] and not just one part. In this submission, I contend that the proposed changes need to:

- Hold employers to account to ensure this change really works for New Zealanders;

- Ensure governance focuses tertiary leaders on community defined success measures;

- Ensure that investment in tertiary education benefits all New Zealanders;

- Invest substantially in the organisational and system changes needed for the new model to succeed;

- Create in the system a new culture of collective engagement in quality improvement rather than accountability; and

- Engage proactively with the implications for the entire tertiary system.

Hold employers to account to ensure this change really works for New Zealanders

Structural problems in the New Zealand economy and in the funding model have driven the system to act in ways that have created many of the problems identified in the Cabinet Paper.

OECD data on spending on tertiary education [7] show that New Zealand education is disproportionately funded from the public resources in comparison to countries such as Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia. Longitudinal data show that despite the public rhetoric regarding skill shortages private investment in tertiary education has remained unchanged over the last decade and is very low in proportion to the GDP in comparison with other similar economies. Within my own family, I have seen younger family members treated very badly by trade employers who are unwilling to sustain the investment in trade qualifications, preferring to employ unqualified staff not in training, something that ultimately damages that employees chance of future advancement in the industry. Another illustration of employer disengagement from their workers is the Treasury finding [8] that young people who gain qualifications are not paid more as a result.

The low investment in New Zealanders by employers is in part a reflection of the dominant neo-liberal ideology [9] that frames the relationship between employers and their staff, and the culture of skill development in this country. The framing of education as a personal responsibility and benefit over the last decade has seen employers able to underinvest in their communities with impunity in the service of economic efficiency and rationalism. Consequently, New Zealanders [10] see a poor return on investment [8] in education in contrast to that obtained by working in other countries. A further complication is that the scale of the New Zealand economy encourages business to look overseas for growth [11], and once their attention shifts from New Zealand it is natural that any significant investment in professional development occurs overseas as well, a problem exacerbated by the foreign acquisition of New Zealand companies by larger ones with head offices in Australia or further afield.

A final influence on employer behaviour is the long-term shift of investment from labour to capital as technological change enables industries to operate at scale with a declining work force. This is a problem for New Zealand as it is clear from Treasury analysis that our economy is undercapitalised [11] and has serious issues with declining human capital [12]. Work by the productivity commission also shows a trend of decreasing labour income share [13] over the last decade consistent with growing inequality seen globally. Whether there will be large contractions in the employed population is contested, but there is no evidence that employers are systematically investing in local communities to help mitigate the disruption that is generally acknowledge will occur over the next decade or more. The Treasury analysis suggests that structurally younger New Zealanders are unlikely to be skilled enough to cope with the likely effects of significant change, while the higher skilled people are older and at risk of simply retiring, a problem exacerbated by the Government’s focus on school leavers, rather than the entire population in its Tertiary Education Strategy and priorities (see below). The changes to employment patterns are also very likely to further increase inequality [10] as the affected jobs are disproportionately dominated by women, Māori and Pasifika New Zelanders.

The framing of this situation in the Cabinet Paper Para 3 reflects some of the points made above:

"Vocational education can help to ensure that all New Zealanders have the skills, knowledge and capability to adapt and succeed in a world of rapid economic, social and technological change. It can improve people’s resilience, employment security and life outcomes, and reduce social inequities, as the trends driving the Future of Work mean they will likely change jobs and careers frequently over their working lives."

However, the currently proposed changes to the provision of vocational education are unlikely to change the calculus resulting in employer disengagement from the responsibility for contributing to healthy and vibrant communities and sustaining the place of education as an enabler of success for all New Zealanders. Further public investment in vocational education without the investment in wage growth by employers will continue to damage the capacity of New Zealand and New Zealanders to succeed as we face ongoing economic, technological and social change.

The cabinet paper states in para 44:

"Employers and industry need to be given, and must take on, a greater leadership role across the entire vocational education system"

Power without responsibility and accountability is unjust and drives inequality. For this leadership role to be meaningful in building a healthy New Zealand society it must include far more effort by employers and industries investing in and supporting our communities, not merely making demands on the public infrastructure extracting profits for private benefit.

Ensure governance focuses tertiary leaders on community defined success measures

Many of the problems facing the tertiary system are exacerbated by the poor choices being made nationally and institutionally regarding success and value to New Zealand society. Short term thinking and self-interested decision making by employers described above are not the basis for sound governance of a system critical to the health and well-being of every community. These changes need to be seen as an opportunity to shift power and ownership of tertiary provision away from those who have failed to deliver substantial change to communities, and instead provide a mechanism that empowers communities to define educational success and impact in their own terms.

The cabinet paper recognises only a very small part of this when it states in para 15:

"To ensure a strong regional presence, each region would have a Regional Leadership Committee to identify local skills needs and link with regional economic development strategies and action plans. The committees would have strong local government and industry participation, and representation of and a strategic partnership with local iwi and Pacific communities. I will consult on the name, role and range of responsibilities of these critical regional leadership committees, and how they formally relate to governance and management of the new Institute."

Education has much more to offer than skills and support for economic development. The Council of Europe (1997) describes the importance of education in the Lisbon Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education in the European Region [14]. Education, they state:

"is a human right … which is instrumental in the pursuit and advancement of knowledge, [it] constitutes an exceptionally rich cultural and scientific asset for both individuals and society … should play a vital role in promoting peace, mutual understanding and tolerance, and in creating mutual confidence among peoples and nations [and] the great diversity of education systems in the European region reflects its cultural, social, political, philosophical, religious and economic diversity, an exceptional asset which should be fully respected."

Our understanding of the complex interplay of drivers and outcomes affecting our society, captured in the focus on sustainability and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), should also be reflected in the plans proposed. As framed, it is not clear that local communities have the opportunity to define the key priorities for tertiary education ensuring that the outcomes are sustainable and beneficial in the full sense described by the SDGs. It is not sufficient that the system provides a skilled workforce for an employer, those jobs need to be good ones that offer a potential for future personal and community growth in wellbeing, and that create and sustain economic activity that protects the full range of community values.

For the proposed changes to be successful, the definition of success must be owned by the entire community with measures defined locally to respond to local needs.

Ensure that investment in tertiary education benefits all New Zealanders

The proposed changes need to acknowledge and address a major shortcoming with the focus and priorities of the educational system over most of the last decade. The focus on school-leavers as a priority group was a well-intentioned attempt to address a major social problem following with global financial crisis. Unfortunately, it has seen the Government and its agencies lose sight of the importance of the whole-of-life value of education. Consequently, tertiary organizations are now vulnerable to the changing age distribution of New Zealand, and older New Zealanders are not receiving the range of depth of educational offerings needed to support their well-being. Setting aside the essential role that education plays in the well-being of communities to focus on the vocational aspects that are the current topic of discussion, the cabinet paper acknowledges the need to address lifelong education and work transitions (para 38):

"An increasingly dynamic labour market means people will likely change jobs and careers frequently over their working lives. Skills shortages will arise in different regions and sectors of the economy, as job displacement occurs in others. Our education system at all levels must be better prepared to respond to these trends, and must genuinely support lifelong learning."

Vocational education must address four major working contexts:

- Entry into adult life and transition into employment;

- Development of specific skills related to employment activities, including new processes, tools, etc.;

- Career development into senior roles with wider skills and responsibilities including leadership, management and entrepreneurial activities;

- Career transition into new directions that do not directly draw on prior experience.

More importantly, the changes to the tertiary system need to recognise the role that education plays in key transitions in the non-vocational aspects of lives:

- Entry in to adult life and transition into socially valued adult responsibilities;

- Development of specific skills needed to enact adult responsibilities and maintain wellbeing;

- Development of skills and knowledge needed to take on senior roles in the community;

- Life transitions including responding to major shifts in personal circumstances and those of the immediate family/social group and the wider community.

Particularly in regional New Zealand the ITPs are a vital element of the social infrastructure of communities which needs to be operated and sustained to build the well-being of the entire community. The delivery of formal qualifications is merely one part of the range of services and experiences that an effective tertiary education provider should be enabling for their communities. The statement made in para 37 of the cabinet paper needs to be placed in whole of system context not limited to those in employment, and recognising its necessary inclusion of those who have needs other than employment:

"At the heart of the Government’s vision for education is ensuring all New Zealanders have the skills, knowledge and capability to adapt and succeed in a world of rapid economic, social and technological change."

An example of a powerful model that has operated successfully in New Zealand is that of the provider who used their facilities cleverly to build intergenerational contacts and support community safety and needs. This provider offered two programmes in close proximity. One was a digital creativity programme with modern music, video and media facilities. The other was a programme on Tikanga for emerging Kaumatua. Both of these operated formally in the first part of the day, with students mingling for meals and breaks. In the afternoon, the digital facilities were provided for local school students to use. Kaumatua were encouraged to remain and interact with both groups of students informally throughout the day. The result was a powerful model of engagement across generations that reduced local crime and misbehaviour, and built well-being and social cohesion in all of the participants. This type of provision, driven by community outcomes rather than commercial investment returns, must be enhanced and rewarded by the new system for it to meet the real needs of our communities.

Invest substantially in the organisational and system changes needed for the new model to succeed

The cabinet paper acknowledges (para 75) the "weak governance and management capability in parts of the sector." The inability of sector leaders to place their organizations within a wider public-good framework has been identified by the Productivity Commission16 and is clearly illustrated by the public statements made following the announcement of this change. Investment is needed to enable a shift in the operational systems, processes and capabilities of the current system. The basic infrastructure of teaching spaces, networks and educators is in place, the challenge remaining is one of management and leadership. The system-wide changes proposed by the Minister will require a substantial development of organisational capabilities and systems to be realised. This will necessarily require investment in three major phases: Pre-implementation; Transition; and Post-implementation.

Pre-implementation of the proposed changes reflects the system investment needed to sustain the operation of existing providers so that students and communities are not disrupted, further than already evident, by the political and media processes of engagement and planning. Irrespective of the structures used to enact the new model, it seems very likely that the scale of current provision will need to be sustained over the next 2-3 years (reflecting the duration of normal qualification study lengths and the time needed for a new system to be implemented). There is a very high risk that staff needed to sustain this will leave the system seeking greater certainty and less stress in their employment, compromising both the ability of providers to sustain current operations and to implement desired changes.

The Minister needs to act decisively again to provide employees of ITPs and ITOs certainty of the need for their skills and experience in any future by funding all existing providers sufficiently to sustain currently levels of employment until at least the end of 2020. Retrenchments and other initiatives driven by poor funding levels and reduced student enrolments are a symptom of the problem being addressed, they need to be responded to urgently in order to allow the system to confidently engage in this major change programme.

The transition to new models of operation will be expensive and complicated. As just one example, there are more than a dozen nursing programmes operating across New Zealand with different curricula, assessments, learning materials, and facilities. The process of changing all of these to a single, nationally coordinated and coherent offering will require substantial work to design a new programme, have it accredited, resource the redevelopment of materials and assessments, train teaching staff in the new approach, and create the operational systems needed to sustain delivery. All of this work needs to occur in parallel with the ongoing delivery of existing courses to avoid disruption to current students and their employers.

This is merely one of the many similar programmes operated throughout New Zealand requiring such change to occur. Significant investment will be needed to fund this change and to provide the opportunity for internal and external stakeholders to lead the design of the new model. The capacity of the system to undertake this transition is another reason why the existing workforce needs to be protected through the pre-implementation period. Much of the reform proposal is predicated on a high level of collaboration and engagement between the tertiary system and the communities served. This is an expensive process if done effectively. Some savings will be realised through the reduction in unnecessary marketing promoting a brand for each provider, but the need for resources helping communities take advantage of educational opportunities means that modest investment in communications will remain.

Post-implementation investment will be needed to ensure the new system delivers the necessary scale of change needed into the future. The financial challenges faced by the ITPs in particular are in part a result of sustained reductions in the real level of funding provided to the system. Business as usual funding needs to be significantly higher than it has been in recent years to ensure that the system is operated on the basis of need rather than on a risk management basis with leaders focusing on surviving crises rather than improvement. Much of this increase should be funded by direct taxes or levies on industry and employers, particularly those that are not operating substantial in-house vocational programmes, and are instead depending on the public purse to fund their skills needs.

Create in the system a new culture of collective engagement in quality improvement rather than accountability

Throughout all three phases (Pre-implementation; Transition; and Post-implementation) significant investment in the development of an effective quality improvement culture and supporting systems is essential. It is notable that no mention is made in the cabinet paper of the significant implications for the NZQA of the proposed change. The current External Evaluation and Review process is poorly aligned to the operation of a national provider as envisioned in the current proposal, and the operation of a disconnected external agency quality process an inefficient way to operate the quality processes of what is effectively a new government agency. Existing quality processes observed in the sector are predominantly bureaucratic and aimed at satisfying external accountability and financial risk management rather than aimed at informing a culture of internal engagement with quality improvement and responsiveness to community needs [15]. The 2017 Productivity Commission report on the tertiary system [16] observed that quality systems have reinforced the status quo and have not stimulated responsiveness to changing needs and the systematic inequalities that continue to disempower students from particular groups.

During the pre-implementation phase investment will need to build the capability of managers and leaders in the sector to engage in quality improvement and support their staff developing and engaging in a positive change and quality culture. This is not able to be done effectively by parachuting in externally designed quality systems or technological process implementations, it is an organisational culture change process that must be collectively engaged in by all staff, as well as key external stakeholders. Creating this positive culture aligned to the change is essential if students are to experience the necessary level continuity required for educational success.

Implementation of the new quality systems and culture is a critical success factor for a successful transition process. This is not a question of enumerating policies and procedures, it is the creation of the awareness of staff of the importance of quality improvements and the enabling the entire organisation to work collectively to that end. The model of quality needed is not one defined by inputs, outcomes or accountability, but rather one intended to support agility, responsiveness and organisational flexibility to the diverse needs of the many different contexts this organisation will need to serve.

Post-implementation, effective quality systems are needed to help a complex and distributed organisation engage with its stakeholders and generate intelligence that guides ongoing improvement aligned to the goals of the local communities. As I have stated in print [17]:

"A key feature of a future focused quality system is its ability to provide guidance and support in real time to the stakeholders of educational systems (students, teachers, employers, educational leaders, government agencies and others) formatively allowing agility, choice and responsiveness in the face of changes in the educational environment, rather than reporting summatively after the moment to act has passed."

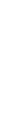

The questions in Table 1 show a sensemaking approach that can be used to frame a view of quality in the new organisation that responds to these drivers and helps establish a self-sustain cycle of data gathering, analysis, reflection and improvement. An advantage of this approach is that it can be used throughout the change process as a tool for engaging with key stakeholders, identifying their concerns and objectives for the change, and supporting the managers and leaders enacting the changes locally and nationally in a coordinated manner.

Engage proactively with the implications for the entire tertiary system

The systemic challenges facing the New Zealand tertiary system are not unique to vocational elements, they are symptoms of a forces that are acting internationally on tertiary education [18]. These are:

- Demographic and political changes driving the scale and scope of tertiary education including increasing globalisation in all forms of commerce encompassing the movement of people and ideas and education;

- Internal and external stakeholder influences. Many, varied and often in conflict with each other, these are changing as the place of tertiary education in society evolves;

- Financial challenges and constraints in terms of access to resources, the diversity of sources of revenue, and the changing role of Government and its positioning of public funding;

- The perception of the value of resulting qualifications and the role reputation and models of quality play in shaping the nature of educational organisations;

- Technological innovation of pedagogy and of the organisation itself. The challenge of understanding the contribution technologies can make and realising those opportunities in a complex organisation.

These act from without the organisation and require responses that act both within and without individual educational providers. The Government has the opportunity with this change to coordinate responses that can address both internal and external features of these forces, but in so doing needs to explicitly address the entire tertiary system, not just the vocational aspects. These are not resolvable by technological quick-fixes such as microcredentials or improved learning management systems, they reflect the complex interconnections between education and society at large, enacted through human desires for better lives for themselves, their families and their communities.

As discussed above, tertiary education in New Zealand is dominated by degree provision and the current environment is very much shaped by competitive aspects that drive people towards more prestigious providers of degrees and towards higher degrees. This is clearly apparent to those of us working in the system where we see institutions constantly changing qualifications in response to these drivers. Most recently this is seeing the shift towards 1 year taught Masters degrees as a product explicitly designed to appeal to an international student market eager to gain a higher degree as efficiently and cheaply as possible. More generally, degrees are attractive to people interested in travelling, as they provide a highly portable qualification recognised internationally with no additional effort, something that is not typically true for vocational qualifications. Degree provision is dominated by the universities and failing to include a plan for their place in a reconfigured national tertiary education system risks placing additional stresses on the new vocational organisation as it engages in the proposed changes.

Brown [19] describes the features a healthy education system needs to address the pathologies created by excessive marketization such that which characterises the New Zealand tertiary education system, stating that:

- It will be valued both for its "intrinsic" qualities in creating, conserving and disseminating knowledge and for its "extrinsic" qualities in serving broader economic, social and cultural goals. Responsibility for determining the system’s "academic agenda" is shared between institutions and external stakeholders;

- There is also a balance between the public and private purposes and benefits of higher education;

- There is a balance between the interests of individual institutions and groups of institutions, on the one hand, and the system as a whole, on the other;

- These is sufficient diversity of provision to enable the system to respond effectively to new kinds of demands, especially for new kinds of learning opportunities;

- Any significant status or resourcing differentials between individual institutions or groups of institutions are confined to, and justified by, "objective" factors such as local cost differences;

- The student population is broadly representative of the population as a whole;

- The staff are well-qualified, well-motivated and well-managed;

- There is a productive and mutually beneficial relationship between the core activities of institutions: student education and academic research and scholarship;

- Institutions are adequately funded for their core activities whilst having plenty of incentives to diversify their funding and make the best use of their resources;

- The system is effectively regulated in the public interest so that it produces worthwhile outcomes for both external and internal stakeholders.

While these are constructed from the University perspective there is much in this that should be guiding changes to any part of the system, given the way that policy changes designed to influence one aspect typically generate unanticipated changes to the rest of the system given its "wicked" state. The current models of agency and sector engagement need to be revisited to ensure that all parts of the system act in the common public interest of New Zealanders and New Zealand communities.

Conclusion

There is a parallel between the proposed model and the Californian model created by Clark Kerr in the 1970s [20]. A key feature of the California model was the recognition that the system needed to respond to a diverse set of communities and students and deliver a range of outcomes. It operated holistically with resources invested in a network of provision that enabled students to receive an education aligned to their personal potential and needs. Individual campus locations were sited to meet local needs and students were guided through pathways that ensured they received a good education aligned to their needs and capability, rather than their social position and family connections. This system has started to fail as a result of the forces identified above. The growing inequality of US society drove underinvestment (much as has been apparent in the New Zealand system), qualification inflation and wider economic pressure devalued the more vocational elements of the system operating at community level (as also is evident in New Zealand) while the higher end of the system focused on the elite segments of society and the international student market to the detriment of the needs of Californian communities (also evident in New Zealand). Economic pressures also saw the growth of a range of external commercial actors [21] who benefited in the short term from changes by offering cheaper online qualifications at scale, in the process creating a significant debt issue and devaluing further the value of lower level qualifications.

The proposed changes to vocational education need to be used to shift thinking about the entire New Zealand tertiary system away from the current models to one defined by the idea of a public good infrastructure akin to those used to provide clean water, roads, schools, hospitals and other features of a modern, healthy society. As an alternative to the dominant industrial model of skills and qualification production, national tertiary systems can be framed as social infrastructure with an economic dimension, but not defined purely on that basis.

Provision in each community needs to be operated at the scale needed to sustain all of the educational needs of that community, not just privileged sub-groups, and not only in response to the current economic conditions of that community. A system operating as described in the Cabinet paper risks constantly reacting to conditions after they have impacted negatively on communities, rather than proactively to create positive conditions for the future.

Endnotes

1 Marshall, S. (2010). Change, technology and higher education: Are universities capable of organisational change? ALT-J Research in Learning Technology 18(3):179-192.

2 Neal, T. and Marshall, S. (2008). Report on the Distance and Flexible Education Capability Assessment of the New Zealand ITP Sector. Report to the New Zealand Tertiary Education Committee and Institutes of Technology and Polytechnics Distance and Flexible Education Steering Group. 82pp. [link]

3 Marshall, S. (2012). E-learning and higher education: Understanding and supporting organisational change in New Zealand: Research Report. Wellington, NZ, Ako Aotearoa National Centre for Tertiary Teaching Excellence. 68pp. [link]

TEC (2018). Shaping sector-wide capability through new Investment Toolkit framework. Wellington, New Zealand: Tertiary Education Commission. [link]

4 Marshall, S. (2017). The New Zealand tertiary sector capability framework. Proceedings of THETA: The Higher Education Technology Agenda, Auckland, May 7-10. [link]

5 Marshall, S. (2018) Shaping the University of the Future: Using Technology to Catalyse Change in University Learning and Teaching. Sydney, Australia: Springer. http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789811076190

Marshall, S. (2014). Technological Innovation of Higher Education in New Zealand, A Wicked Problem? Studies in Higher Education. DOI:10.1080/03075079.2014.927849

6 Waks, L.J. (2007). The concept of fundamental educational change. Educational Theory, 57(3), 277-295.

Sandel, M.J. (2013). What money can’t buy: The moral limits of markets. New York, NY, USA: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

7 OECD (2019). Spending on tertiary education (indicator). doi: 10.1787/a3523185-en (Accessed on 20 March 2019)

8 Tumen, S., Crichton, S. and Dixon, S. (2015). The Impact of Tertiary Study on the Labour Market Outcomes of Low-qualified School Leavers. Wellington: The Treasury.

9 Larner, W., and R. Le Heron. 2005. "Neo-Liberalizing Spaces and Subjectivities: Reinventing New Zealand Universities." Organization 12 (6): 843–862. doi:10.1177/1350508405057473.

Wheelahan, L and Moodie, G. (2017). Vocational education qualifications’ roles in pathways to work in liberal market economies. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 69:1: 10-27, DOI: 10.1080/13636820.2016.1275031

10 Zuccollo, J., Maani, S., Kaye-Blake, B. and Zeng, L. (2013). Private Returns to Tertiary Education: How Does New Zealand Compare to the OECD? Wellington: The Treasury.

11 New Zealand Treasury (2008). Investment, Productivity and the Cost of Capital: Understanding New Zealand’s "Capital Shallowness." New Zealand Treasury Productivity Paper 08/03. Wellington: The Treasury.

12 Morrissey, S. (2018). The Start of a Conversation on the Value of New Zealand’s Human Capital. Wellington: The Treasury.

13 Fraser, H. (2018). The Labour Income Share in New Zealand: An Update. Wellington: New Zealand Productivity Commission.

14 Council of Europe (1997). Convention on the recognition of qualifications concerning higher education in the European region. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe (p. 1). Retrieved from http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/165.htm

15 Marshall, S. (2017). The New Zealand tertiary sector capability framework. Proceedings of THETA: The Higher Education Technology Agenda, Auckland, May 7-10. [link]

16 New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2017). New models of tertiary education: Final Report. Available from http://www.productivity.govt.nz/inquiry-content/tertiary-education

17 Marshall, S. (2016). Quality as sense-making. Quality in Higher Education. DOI: 10.1080/13538322.2016.1263924 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13538322.2016.1263924

18 Marshall, S. (2018) Shaping the University of the Future: Using Technology to Catalyse Change in University Learning and Teaching. Sydney, Australia: Springer. http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789811076190

19 Brown, R. (2011). Higher education and the market. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

20 Marginson, S. (2016). The Dream is Over: The Crisis of Clark Kerr's California Idea of Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: University of California Press.

21 United States Senate (2012). For profit higher education: The failure to safeguard the Federal investment and ensure student success. Washington, DC: United States Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee.