The Real University Challenge - Having Wages That Reflect Qualifications

The recent op-ed on Stuff by former Minister and VC Steve Maharey places the blame on the sector – I think we need to look slightly further afield and listen to the people making these choices.

School leavers are increasingly questioning the costs of gaining tertiary qualifications. The reason they’re doing so is the reality that gaining a qualification in New Zealand doesn’t generate the financial rewards necessary to justify those costs. You just have to look at the revolting comparison between the salaries offered for minimally skilled work and for jobs requiring qualifications and making far greater demands on the people working in them reported by Stuff earlier this year (the table at the end is an indictment of the Government and employers).

New Zealand is struggling with the ongoing financial and social challenges exacerbated (not caused I emphasise) by the pandemic. The education system is not immune, particularly as the process of establishing Te Pukenga drags on. One of the symptoms of the failing state of the NZ system (and others) is evident in the long term participation trends.

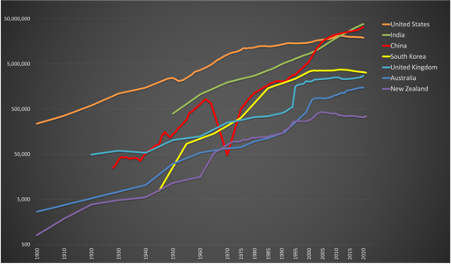

The figure (prepared using OECD data and local government reporting) shows the difference between the two growing systems (China and India) and those that show a shift to stalled pattern (including New Zealand). One of the contributors to this decline is demographics but as the next figure shows it’s not the only contributing cause in New Zealand:

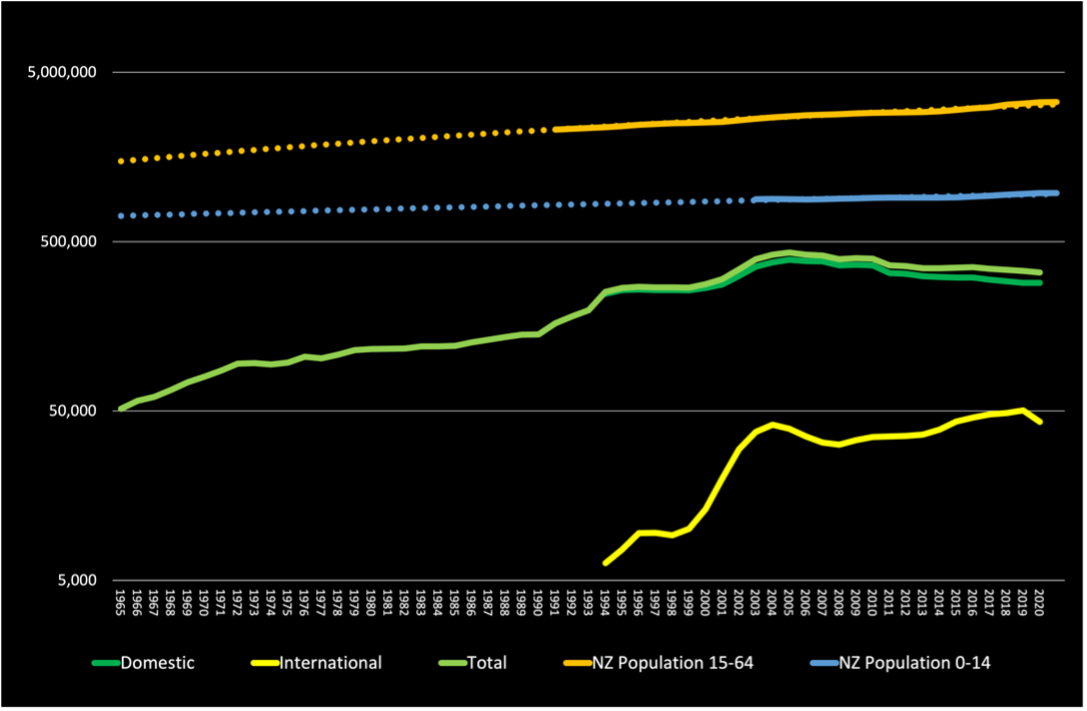

New Zealand’s population is still growing steadily as can be seen by the gentle upwards trajectory of the orange line (adult population) and blue line (young population). The problem facing the education system is the widening gap between these lines and the green line which shows the steady decline in domestic student numbers. Students are increasingly choosing to not engage in tertiary education.

I place the blame firmly on employers who are choosing not to invest in New Zealanders and are instead influencing politicians in both major parties to sustain a low-wage economy. It’s all too easy and cheap to place all of the cost of education onto individuals and the taxpayer, and to use immigration to attract skilled foreigners from lower-wage developing economies, rather than business owning the social responsibility of building the entire economy.

Making the situation worse is the structure of the NZ economy which sees many larger enterprises focusing more on Australia, either as they grow into that larger market, or as they get acquired or run as branches from there. Either way, with head office attention not on NZ, it's easy to see why any investment in R&D or development of staff happens disproportionately outside of NZ and why cost-minimisation (profit seeking) dominates their remuneration strategies domestically.

How to fix it?

I think we need to help employers in New Zealand understand the necessity to invest in New Zealanders in the way that countries like Germany do. My suggestion is that a payroll tax be levied on all employers with more than a small number of staff, at a sufficient rate to really get their attention. This would be balanced by a generous rebate for any direct expenditure in staff studying at New Zealand tertiary institutions for formal qualifications – say 120% of the actual fees, allowances and time off paid by the employer for staff gaining further qualifications on the job, and an even more generous 150% for people without any qualification gaining their first one. Neither of these would be available for employers who impose restrictions on staff leaving – golden handcuffs – or that make staff repay the costs of education when leaving.

This would help by directly driving investment into training and skill development helping reduce the cost of education locally and also indirectly by creating an incentive for employers to be more engaged with tertiary providers to ensure that what is taught and how it is taught has the most benefit. Over time it should also see wages grow as the base skill level of our society rises and educated people use their skills to grow their own careers – wise employers will want to keep staff locally rather than see their investment walk out the door and off to better paying roles overseas.

The solution to the challenge of raising the skill levels, wages and quality of life of all New Zealanders is one that requires contributions not just from tertiary organizations and their staff, or the Government. It is not one that gets solved by local employers telling the system what they want without taking on the financial consequences (i.e. Te Pukenga’s WDCs) nor is it resolvable by the sorts of minimal tinkering Maharey’s disorganised list presents. We need industries and employers prepared to seriously commit to New Zealand as more than a community to be exploited, they need to invest meaningfully in our collective educational future.